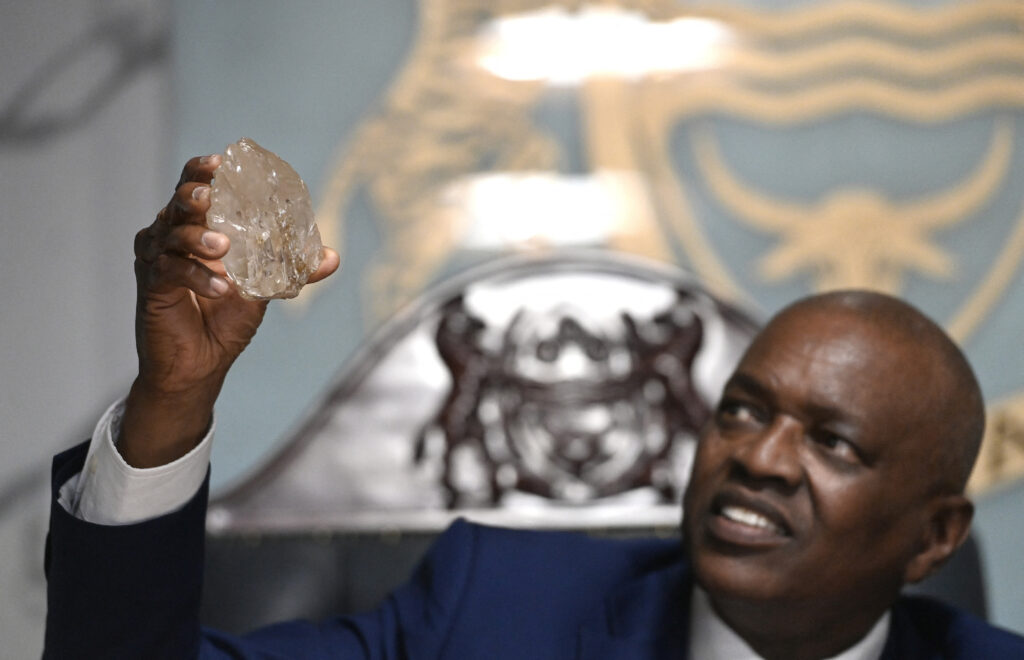

The recent huge diamond find in a mine in Botswana could not be better timed to renew the sparkle of a luxury sector plagued by flagging sales and struggling to outshine consumer demand for synthetic alternatives. Discovered by Canada’s Lucara Diamond at the Karowe mine this August, the 2,492-carat rough diamond is the biggest gemstone-quality discovery for about 120 years. The previous whopper, the Cullinan Diamond unearthed in 1905, was cut into faceted gems and now forms a part of the British Crown Jewels – putting the enormity of this recent discovery into historical perspective.

The potential of a fillip to the natural diamond market is much needed as industry sources suggest prices have dropped by more than 30% since a peak in early 2022. Such was the concern in the sector that last October De Beers suspended all online sales for rough diamonds in a bid to halt the slide. Other major players also ceased auction sales last year to suppress supply.

“The demand for [natural] diamonds has declined as its allure fades in a key consumer market, China,” says Sam Kima, Senior Vice-President of First Gold. “Falling marriage rates as well as growing popularity for gold and lab-grown gems all drove down Chinese demand for diamonds.”

He also points out that despite Indian manufacturers reducing production, sales fell at a sharper rate due to weak demand. India is thought to cut and polish about 90% of the world’s rough diamonds. “This led to an oversupply and pressure to sell. Synthetics continued to take market share from natural diamonds and will likely do so throughout 2024,” he opines.

Synthetic alternative

Kima suggests the price dynamics of lab-grown diamonds (LGDs) are offering affordable alternatives to consumers on a budget. “A natural stone costs roughly US$2,500, versus about US$500 for a same-quality lab-grown equivalent,” he says. “A natural two-carat round-cut diamond with a high-quality colour and clarity rating costs about US$13,000-14,000, whereas the equivalent LGD sells for about US$1,000.”

He also highlights that loose LGD sales soared 47% in 2023 compared with one year earlier.

“Theoretically, the only limitation on the supply of LGDs is the rate at which they can be made. With demand increasing, more producers are entering the LGD market and prices are dropping even further.”

Industry analysts have speculated that the boom in LGDs may now have peaked, and there are reports that some retailers are switching back to natural stones to boost profitability and margins. “Demand remains robust for natural diamonds and while they are much rarer than lab-grown, their supply is also quite tightly controlled so that prices stay robust,” says Kima.

He also questions how sustainable synthetic diamonds really are, calling for further research, and highlights other advantages of natural stones: “There is a unique rarity about natural diamonds and the journey they go on before becoming beautiful pieces of jewellery. The initial investment for a natural diamond may be higher, but their timeless elegance will never go out of style, or value.”

He insists that LGDs do not have the rare qualities and long-lasting value of natural diamonds, or their sentimental value and potential for investment. He says consumers should make up their own minds based on their values, budget and the significance of tradition, and warns that consumers should be aware of misleading marketing.

Natural shift / Lab implosion

David Kwok, founder of Absolute Luxury, a strategic consultancy dedicated to premium and luxury jewellery brands, thinks retailers will progressively move away from LGDs. In his view, the gigantic volumes required to sustain the lab-grown business to cope with the current economic environment has created a “vicious circle”.

Though manufactured diamonds now account for a sizeable chunk of the jewellery market, the dramatic 90% drop in LGD prices from $300 to $30 per carat is causing many players in the industry to reassess their role. In June, De Beers announced that it has ceased production of synthetic diamonds for its Lightbox jewellery brand and will instead manufacture and sell natural polished stones. “We believe the value of lab-grown diamonds lies in technology rather than in jewellery,” said Al Cook, CEO of De Beers Group.

Kwok cites the example of Israeli venture Lusix, which attracted funding from LVMH Luxury Ventures just two years ago, as a precautionary tale. “Lusix, a pioneer in LGDs, raised US$90 million in 2022 with high hopes for its ‘sun-grown diamonds’. Fast forward to today, the company is on the brink of insolvency,” he says.

He puts the recent plunge in prices of natural diamonds into perspective. “The industry had been one of the great winners of the global pandemic; stuck-at-home shoppers turned to diamond jewellery and other luxury buys,” he explains. “But as economies opened up, demand quickly cooled, leaving traders holding too much stock. This quickly turned into a plunge.”

He also cites inflationary pressures in the US economy and sapping consumer confidence in China as major factors in declining demand. Yet he believes the true value of natural diamonds is becoming increasingly clear, and despite initial enthusiasm, LGDs have failed to replace natural diamonds in the luxury market.

Fancy fortunes

Roi Sheinfeld, Managing Partner of diamond manufacturer M&B Group, affirms that natural diamonds will always hold that special allure for luxury consumers given that they are billions of years old. “This is especially so for well-cut fancy shapes and fancy-colour diamonds; they are always in shortage, and each of them is unique and different. Nothing can replace this,” he says.

He has not experienced a big drop in prices in the larger, higher-end fancy-colour diamonds over recent times, and believes there is no substitute for natural diamonds. He does, however, retail the synthetic version as well.

“Lab-grown diamonds are fun, and they are great for anyone who wants to wear fun jewellery without breaking the bank account or to be concerned about the safety of wearing very expensive jewellery,” he says, while indicating that it is the responsibility of retailers to explain that LGDs do not pose a resale value.

Sheinfeld is optimistic about the potential impact of the Botswana discovery on the wider impact for the diamond sector. “It’s an outstanding historical discovery and definitely puts a spotlight on diamonds and how important the industry is,” he enthuses. “I tend to agree with others in the industry that, in contrast to most rough diamonds, [this stone] will retain more value if kept uncut as a true historical collector’s item.”

Collectors’ market

Speculating on the possible buyer of the world’s second-largest gem-quality diamond, he opines: “If sold to be cut-and-polished, my best guess is that a big-name brand will make a whole collection from the polished outcome. If kept unpolished, some very lucky collector will be the happy new owner!” Indeed, it has been reported that Lucara has been inundated with enquiries since the stone was found, and it was exploring luxury brands, museums, collectors and royal families as potential buyers.

Kwok also believes the find will boost the luxury diamond market and is bullish about the broader prospects of Botswana, which has used its diamond resources wisely since independence in 1966 to build schools, roads and hospitals. He says these monster diamonds from deep in the earth – or clipper diamonds (Cullinan-like, Large, Inclusion-Poor, Pure, Irregular and Resorbed) – are typically acquired by the wealthiest 1%, possibly at a prestigious auction sale as a collector asset. High jewellery houses and large jewellery groups, private trusts, investment companies and family offices are also potential buyers.

Interestingly, it was Louis Vuitton which scooped up the newly unearthed 1,758-carat Sewelo diamond in 2020, the world’s second-biggest sparkler at the time. Kima notes: “Louis Vuitton bought it for an undisclosed sum, even though it was black in appearance and it was unclear how many gems could be cut from it.”