Bhutan has until relatively recently lived in glorious isolation, in part due to the challenges of its geography and monumental topography. Wedged between India and the autonomous region of Tibet, China, the Buddhist kingdom has been likened to a gigantic staircase, rising from a narrow strip of land at an altitude of 300 metres in the south to more than 7,000 metres in the north. Its bounteous natural wonders are at their glorious best from late September through December when weather patterns are stable. These months also see some of the best festivals playing out in all their intoxicating magic.

Many of the 790,000 inhabitants of this landlocked state still live off the earth, though there is a growing middle class in urban areas. The capital and most populated city, Thimphu, houses about 15% of the population, and the government is making strides to limit migration from the countryside.

National happiness

Though Bhutan is rapidly modernising and introducing new technology and industrial advancements, the government famously places the concept of Gross National Happiness as a high priority. With the tenets of Buddhism shaping national policy, mindfulness, compassion and well-being, as well as sustainable development, education, health care and good governance are valued above economic growth – which is perceived as a way of achieving more important ends. The country’s coffers are boosted by a daily visa fee of US$200 per visitor.

Religious pageantry

Throughout the year Bhutan’s many dzongs (fortresses) and goembas (monasteries) play host to colourful religious festivals that are adored by travellers and locals alike. These pageants enable the people to immerse themselves in the meaning of their religion and Buddhist teachings.

Constructed at strategic points for political reasons, the dzongs nowadays contain both regional monastic communities and district administrative offices. Some consider these majestic buildings the most beautiful architectural forms in Asia, with their richly decorated woodwork and ethereal pitched roof held within a solid structure of elegant sloping walls.

Tshechus (festivals) are grand social events representing an opportunity for locals to see and be seen. A holiday atmosphere pervades, people wear their finest jewellery and clothes, share their food and exchange news. They take out picnics rich with meat and copious quantities of alcohol.

Masked dance

At the heart of the tshechus are religious dances called cham, performed by monks or lay practitioners wearing spectacular costumes made of yellow silk or rich brocade. Sometimes they don masks which represent animals, fearsome deities, skulls or manifestations of Buddhist gurus. These masks can be so heavy that the performers often bind their heads with strips of cloth to support the weight and protect themselves against injury.

One of the best known, the Drametse Ngacham (Mask Dance of the Drums from Drametse), has been proclaimed as a masterpiece of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by Unesco. The epic display features 16 energetic male dancers dressed in yellow skirts and animal masks and beating drums.

Many tshechus culminate in the unfurling of a giant thangka from a building overlooking the dance arena. Upon sight of these painted or embroidered religious pictures, it is believed that all one’s sins are washed away.

The dates and duration of tsechus vary from one district to the next and are usually performed in dzong courtyards thronging with entranced onlookers. For the grand Thimphu Tshechu festival, held this year on 13-15 September, the capital takes on a carnival air.

A sacred seventh-century monastery in the Bumthang Valley is the setting for the Jambay Lhakhang festival (15-18 November 2024), where a naked fire dance held under the full moon at midnight kicks off the vibrant proceedings. November also sees smaller-scale Trashigang, Jakar and Mongar tshechus, while December welcomes the Trongsa, Lhuentse and Dungkhar festivals.

Architectural splendours

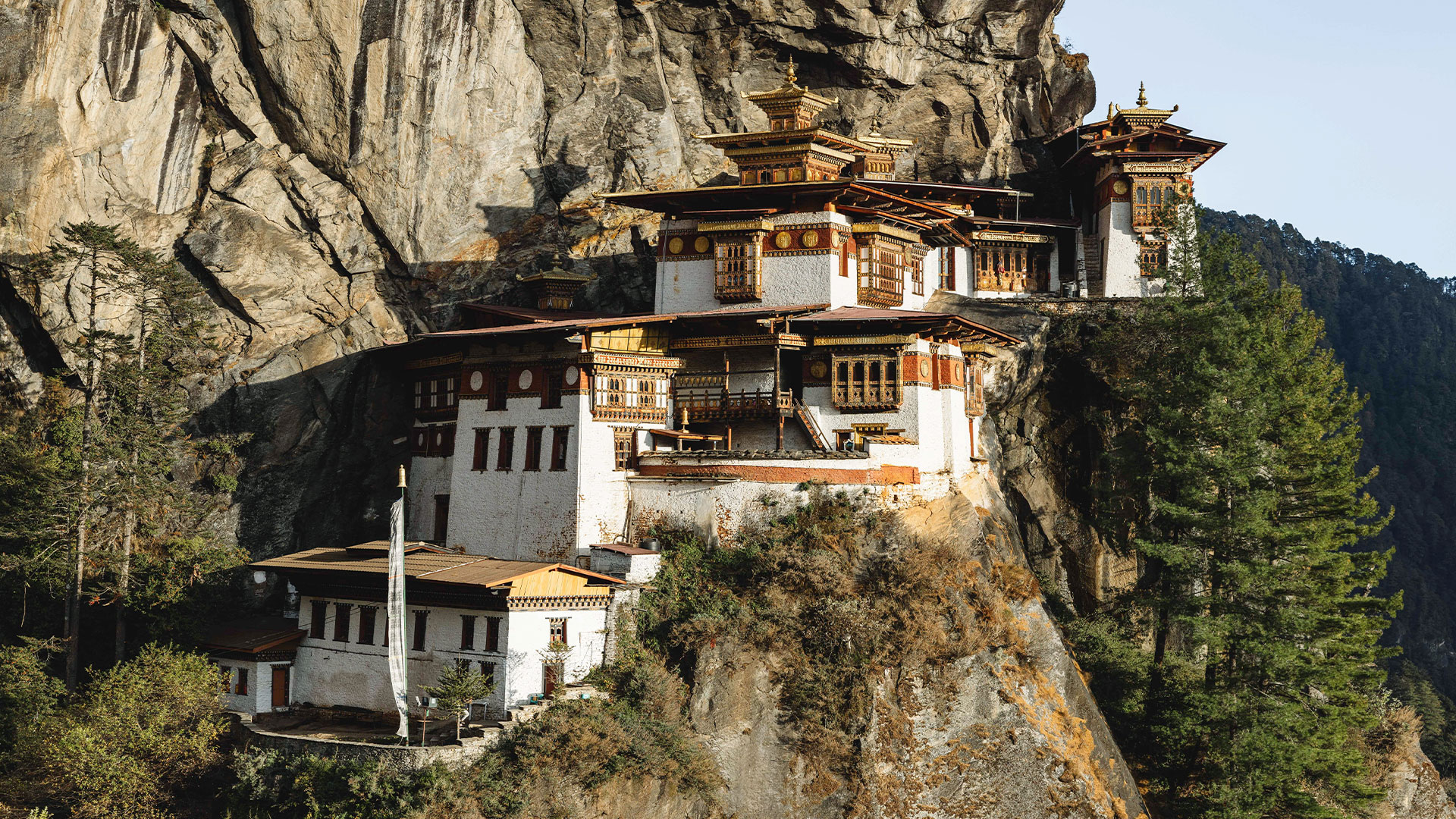

Aside from the magnificent festivals, the splendours of Bhutan’s monasteries and dzongs are legendary, not least Taktsang Goemba, a beautiful building clinging to the side of sheer cliffs perched above whispering pine forests. The site has deep religious significance; legend has it that Guru Rinpoche, a founding father of Tibetan Buddhism, rode here on the back of a tigress to subdue a local demon, after which he embarked on three months of soothing meditation. It is well worth a visit, offering incredible views of the Paro Valley on the trek up past glorious red-blossom rhododendrons.

Paro’s Rinpung Dzong is a fantastic example of a fortress-monastery that majestically guards the valley and town. Above the dzong is an old watchtower, the Ta Dzong, which has been converted into the hugely informative National Museum of Bhutan.

Not far from the gateway town of Paro amid an attractive area for walks is Kyichu Lhakhang, a twin-temple complex whose first building is thought to have been completed in 659 AD by King Songtsen Gampo of Tibet. Inside this magnificent complex sits a treasured seventh-century statue of Jowo Sakyamuni.

Overlooking the labyrinthine Trongsa Dzong in central Bhutan, the seat of power in the first and second centuries, is a museum dedicated to the history of the dzong and the Wangchuck dynasty, replete with personal effects and Buddhist statues.

At the confluence of two rivers resides Punakha Dzong, one of the most striking examples of Bhutanese architecture. Every spring, the fortress walls are covered in lilac flowers from nearby jacaranda trees, and hordes of red-robed young monks can be seen wandering over a sea of purple petals.

Fantastic trekking

Bhutan is also reputed for its world-class trekking. Many treks reach high altitudes in remote regions of the country’s spectacular Himalayan range, and come with guides and ponies to carry your pack. One of the well-trod Jhomolhari routes within Jigme Dorji National Park entails a two-day gentle climb with just a few short, steep rises over side ridges. The remote village of Lingzhi is accessed by crossing a high pass, and to reach Thimphu yet another high pass is traversed.

Along the popular Snowman trek, similarly away from roads and modernisation, are plenty of chances to glimpse locals tending their crops and animals in the centuries-old tradition. A five-day trek to Duer Hot Springs is an alternative ending to this exhilarating excursion.

Day hikes to monasteries in the cultural heartland of Bumthang are also an option in a region full of valleys nestling dzongs, goembas and temples. The Haa Valley is also a great place to do some trekking. Just a few hours’ drive from Paro, it offers cliffside hermitages, ancient temples, charming villages and accommodation in boutique farmhouses and homestays.

Wildlife protection

A member of the Climate Vulnerable Forum, Bhutan is an environmentally aware society, with immense sources of renewable energy in the form of hydropower; however, melting glaciers caused by climate change are a growing concern.

The country treasures its wildlife and has one of the largest proportions of designated protected areas in the world. With more than 65% of its territory covered in forests and mountains, this wildlife haven offers an amazing diversity of plants and creatures. Scarce species of bird can be glimpsed, or you might spot a troupe of rare golden langurs. In spring, beautiful splashes of red, pink and white dot the landscape in the form of ubiquitous rhododendron.

The national dish, ema datshi, is composed entirely of stewed chillies served with a cheese sauce. Indeed, melted fresh datshi (cottage cheese) cooked along with vegetables, especially potatoes, mushrooms, asparagus and fiddlehead ferns, is a key component of the local diet. This is a spicy delicacy normally served separately in deference to visitors’ taste buds. Rice (white or red) dishes and stews also form a central plank of cuisine in this kingdom of fabled fortresses, festivals and treks.