Virtual reality (VR) is the ultimate example of man meets machine. By simply putting on a VR headset, users can escape the real world and explore pretty much anything in the virtual world. All achieved with ever-improving electronic equipment, typically with a helmet and inbuilt screen or gloves fitted with sensors.

But where did VR originate? The term ‘virtual reality’ was coined by web pioneer Jaron Lanier in 1987, but the concept had been around long before that. In the 1950s, when people still watched black and white TVs and Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor and Elvis were wowing the public, American inventor and cinematographer Morton Heilig invented the first interactive multimedia device, the Sensorama, in 1957.

Heilig’s invention gave users the illusion of reality by immersing them in a 3-D motion picture with smells, stereo sound, seat vibrations and wind. The viewing holes were surrounded by a series of vents, which were sheltered under a hooded canopy. The 3-D film was viewed through eye portals and filled most of the user’s peripheral vision.

However, as Sensorama was so far ahead of its time, the device was missing the one thing that truly defines a virtual reality experience: a computerised image. Heilig dreamed up his invention long before modern computers and technology caught up to his vision.

In the late 1980s, Lanier’s company – the Visual Programming Lab (VPL) – developed the first multi-person virtual worlds using head-mounted displays, along with the first representations of users within these virtual worlds.

In the late 1980s, Lanier’s company – the Visual Programming Lab (VPL) – developed the first multi-person virtual worlds using head-mounted displays, along with the first representations of users within these virtual worlds.

A true visionary, Lanier also saw the benefits of virtual reality beyond just entertainment. Even though militaries had been using flight simulators for years – the first one was commissioned by the US Air Force in 1966 – to train their pilots on how to fly and to deal with problems in a virtual setting, the use of virtual reality technology outside of entertainment was limited. Lanier cottoned onto this and his team developed the first implementations of virtual reality applications for surgery, vehicle interior prototyping, television production and beyond.

This golden era of virtual reality was to be short-lived, however. Even with the release of breakthrough movies such as Tron and The Lawnmower Man, set in the world of virtual reality, by the mid-1990s, the promise of being whisked away to a different world just by donning a headset was trickier and more expensive than people realised.

It wasn’t like today where people can slip on slim headsets and enjoy VR from the comfort of their homes. People in the ‘90s had to go to an arcade and pay over the odds to sit in a giant pod, wear a huge headset to play a game with substandard graphics and sluggish movement from the avatar – and look totally ridiculous in the process. The VR arcade machines in the 1990s and movies using VR brought the technology to the public’s attention, but it wasn’t enough to keep people interested or make them eager enough to pay for the technology. Unsurprisingly, it slowly fizzled out as a form of entertainment.

It did, however, remain a tool in fields such as medical care and the military. Since 1997, virtual reality has been used to treat patients with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Georgia Tech released the first version of the Virtual Vietnam VR to treat Vietnam veterans with PTSD. Virtual Vietnam allows users to ride a combat helicopter and walk through a hostile helicopter landing zone in Vietnam. The scenes experienced by the vets through Virtual Vietnam helped them relive and process difficult emotions as a way of curing them.

The technology was not just used to help patients. Research teams in the ’90s developed virtual reality scenarios to help surgeons rehearse real or robotic procedures using advanced computer generated images. Surgery simulators have been invaluable for physician training. VR has also been used to help people get over phobias such as a fear of heights and flying.

Due to advancements in technology over the past two decades, VR can now be the immersive experience it has promised. And when Facebook purchased Oculus – a virtual reality startup – in 2014 for US$2 billion (HK$15.5 billion), developers and investors became convinced the technology had a future.

Shortly after the purchase, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg posted on his Facebook wall: “This is just the start. After games, we’re going to make Oculus a platform for many other experiences. Imagine enjoying a courtside seat at a game, studying in a classroom of students and teachers all over the world or consulting with a doctor face-to-face – just by putting on goggles in your home.”

Zuckerberg is not the only one with the idea to make VR a platform for more than just games.

Here in Hong Kong, VR is used for fitness, to sell property and by art galleries.

Pure Fitness spent US$450,000 to build the world’s first 270-degree virtual reality screen in a gym in 2015. Fitness fanatics can enjoy a spin class that immerses them in a world where they cycle through space, up the Himalayas and through the streets of cities. ‘Immersive Fitness’ is clearly aimed at attracting younger people to the gym with loud music and shouty instructors. But it’s also unique, as VR fitness tends to be limited to headsets, and working out alone is arguably not as much fun as exploring the virtual world in a room filled with other sweaty cyclists.

The use of VR in property does the opposite, in a way, to that of fitness as it takes the effort out of property hunting. Potential buyers just have to strap on a headset and they are then whisked away on a virtual tour of the property they are interested in buying. All from the comfort of the property agent’s office. The virtual tours are perfect for people looking for a home but who don’t really have the time to traipse around the streets of Hong Kong.

It is also ideal for people who are looking to buy a house outside of Hong Kong as it eliminates the need to travel. It also suits property agents and developers because all they have to build is a virtual showroom and everything can be contained in the headset rather than in an actual bricks-and-mortar showroom. Developers like Sino Land have taken advantage of the advancement in technology with VR tours of its properties in Sai Kung.

It isn’t just property developers who are taking advantage of VR to make sales. At the recent Art Basel in Hong Kong, the use of VR was a star attraction in and around the event. Google showed off the work of five artists that had used Tilt Brush, its 3-D drawing and painting tool.

The exhibition, Virtual Frontiers: Artists Experimenting with Tilt Brush, was a highly successful presentation of VR artworks by the five artists.

“This collaboration extends Art Basel’s interest in the digital realm and how artists approach this topic on different levels,” said Marc Spiegler, Art Basel’s global director.

“Virtual Frontiers allows internationally renowned artists to experiment with new technology and to expand their practice into another dimension.”

It wasn’t just Google who was getting in on the VR act. Artist Huang Yong Ping made an eight-minute film of his Empires installation, which was viewed through a Samsung Gear headset.

Visitors who donned a headset at Art Basel could decide how close they wanted to get to a piece of art, which aspects of it they wished to view and even move inside the artwork.

Advancements in virtual reality are continuing apace. So whether it’s for purely thrilling entertainment purposes, buying a property or even gleaning a greater appreciation of an enthralling artwork, VR presents fascinating possibilities. Undoubtedly more intriguing developments are just over – and beyond – the horizon.

Text: Andrew Scott

Are you religious?

Are you religious?

For evidence of that fact, look no further than the array of high-end silk products currently on the market. A king-sized silk bed cover by Frette, for example, will set you back US$2,200 (HK$17,300). The Italian brand makes some of the world’s most expensive linens, which have been supplied to luxury hotels around the world, including the Ritz in Paris, the Danieli in Venice and the Peninsula in Hong Kong. The aforementioned silk bed cover displays a chromatic effect produced by yarn-dyed mixed silk jacquard, a process that colours each individual thread, giving the cover a lavishly luminous look.

For evidence of that fact, look no further than the array of high-end silk products currently on the market. A king-sized silk bed cover by Frette, for example, will set you back US$2,200 (HK$17,300). The Italian brand makes some of the world’s most expensive linens, which have been supplied to luxury hotels around the world, including the Ritz in Paris, the Danieli in Venice and the Peninsula in Hong Kong. The aforementioned silk bed cover displays a chromatic effect produced by yarn-dyed mixed silk jacquard, a process that colours each individual thread, giving the cover a lavishly luminous look. While silk has a reputation for being soft and delicate, the fibres that constitute the material are surprisingly strong and durable. This makes it useful in a number of more industrial products, such as electronic insulation coils, suture materials for medical use, military-grade parachutes and artillery gunpowder bags, tires and even prosthetic arteries.

While silk has a reputation for being soft and delicate, the fibres that constitute the material are surprisingly strong and durable. This makes it useful in a number of more industrial products, such as electronic insulation coils, suture materials for medical use, military-grade parachutes and artillery gunpowder bags, tires and even prosthetic arteries.

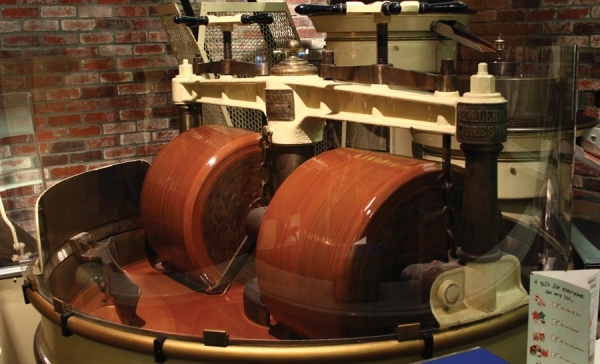

“Some chocolatiers even experiment with distinctly Chinese flavours like fermented bean curd, black garlic and black sesame”

“Some chocolatiers even experiment with distinctly Chinese flavours like fermented bean curd, black garlic and black sesame” “The taste, of course, is important, but I think that the look of it – the shape, as well, and the colour (are equally important),” says Christine Chan, director of business development at Vero. “If you see the Japanese market, the trend is to use a lot of different colours – very sharp, very colourful. People are looking for something more than just plain dark chocolate.”

“The taste, of course, is important, but I think that the look of it – the shape, as well, and the colour (are equally important),” says Christine Chan, director of business development at Vero. “If you see the Japanese market, the trend is to use a lot of different colours – very sharp, very colourful. People are looking for something more than just plain dark chocolate.”