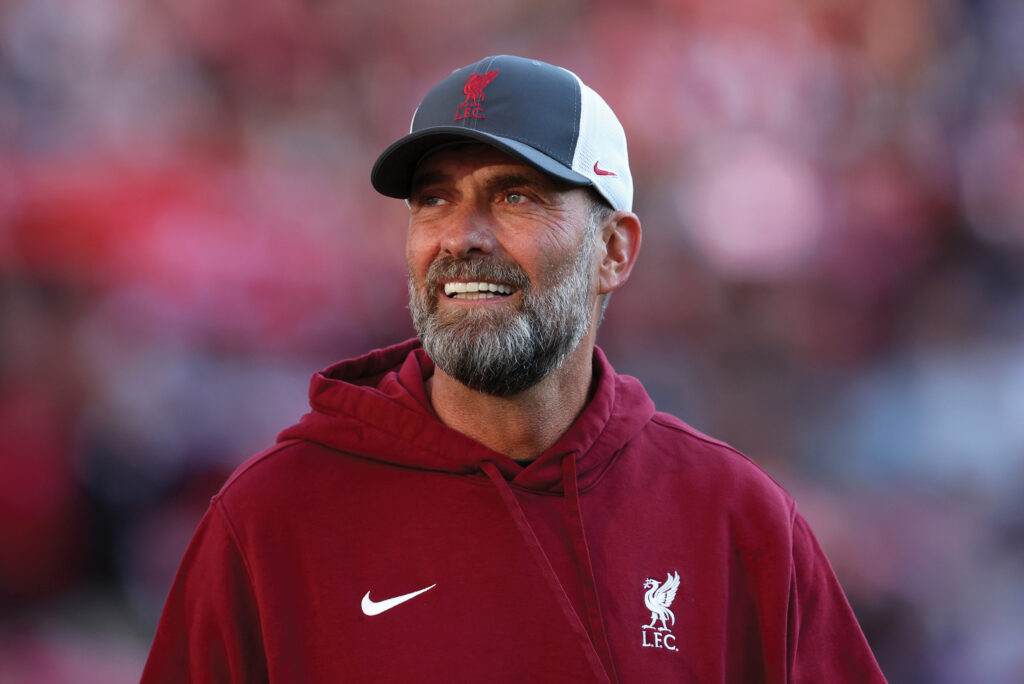

The decision by Liverpool manager Jürgen Klopp to step down at the end of the season came as a shock to the football world and brought to the attention of a wider audience the mental pressure and physical toll exerted by top- tier sports management.

Here is a charismatic leader at the very pinnacle of his profession, who is adored by his legion of fans and has brought fantastic success to Liverpool over the past eight years. Trophies and finals have come in bucket loads. He masterminded in 2019-20 Liverpool’s first- ever Premier League, took his side to three Uefa Champions League finals, winning one, and secured a Fifa Club World Cup title. Only weeks ago yet another final and trophy came his way – an epic League Cup victory over Chelsea.

But the manner of winning that latest final underscores the relentless pressure the drive for success brings. It came with a goal late in extra-time, just two minutes before the dreaded penalty shootout would have kicked in. Playing against a team assembled for megabucks, Klopp was forced to field a crop of untried youngsters due to his squad’s horrendous injury list.

The fact that Liverpool found a way to win can be attributed in no small part to his inspirational management as well as their determination to give him a good send-off. There have been low points during his Anfield tenure, of course; last season the team were poor by their previous high standards and failed to qualify for the Champions League – a stress-inducing scenario for any leader.

Energy sapping

In a brutally honest statement delivered to Liverpool fans and the media in late January, Klopp indicated this constant drive for success was draining his energy levels. “It is that I am, how can I say it, running out of energy,” he declared. “I know that I cannot do the job again and again and again and again.”

There appeared to be no bitterness in this parting of ways, with Klopp adding: “I love absolutely everything about this club, I love everything about the city, I love everything about our supporters, I love the team, I love the staff. I love everything. But that I still take this decision shows you that I am convinced it is the one I have to take.”

Klopp, of course, is not the only high-profile figure in recent years to cite depleted energy levels as the main cause of their departure from a ‘dream’ job. Jacinda Ardern became prime minister of New Zealand in 2017 aged just 37 but resigned five years later, telling the media: “I know what this job takes, and I know that I no longer have enough in the tank to do it justice. It is that simple.”

Low battery

Indeed, some well-being professionals have applauded the honesty of such decisions and the explanations behind them. These are highly successful individuals who felt they were simply no longer able to perform to the maximum of their abilities due to burnout. Jeffrey Kindler similarly quoted the nature of his job as justification when, in 2010, he unexpectedly stepped down from the helm of Pfizer, then the world’s biggest drugmaker. While commentators suggested ulterior motives in Kindler’s case, such as leaving before ignominiously being forced to quit, the very human need to “recharge the batteries” remains a potent line of reasoning.

Senior roles like those occupied by the Klopps, Arderns and Kindlers of this world require unbounded commitment and stamina, endless rounds of meetings and taking decisions that are subject to intense scrutiny. To succeed in such an environment takes a very thick skin and super-high energy levels. To admit to feeling wanting in this regard is both rare and welcome, according to health experts.

Workplace stressors

It is doubtful that Klopp is experiencing the full classic symptoms of burnout, a psychological condition many people have felt sometime during their life. The World Health Organization recognises burnout as an occupational phenomenon resulting from chronic work-related stress that is characterised by feelings of exhaustion, job-related cynicism and lack of professional efficacy. Klopp may be worn out right now, but he remains loyal to and loving of his mode of occupation and is performing to exemplary standards.

Nonetheless, his decision to leave Liverpool highlights the rise of burnout across the developed world. Earlier this year mental Health UK published its first annual burnout report, which revealed that one in five working adults in Britain required time off last year because of stress. It listed numerous workplace stressors contributing to the risk of burnout including high workload, job insecurity and bullying. Contributing factors outside work, such as poor sleep, financial uncertainty, poor physical health and feeling isolated, were also acknowledged.

Burnout prevention

On the flip side, supportive factors which help alleviate stress and prevent burnout included having a supportive network of family or friends, maintaining a healthy work-life balance, and exercising regularly. In its recommendations to minimise the risk of burnout, the report emphasised the need for open dialogue about what a good workplace should look like, and the importance of managing workloads, prioritising wellbeing and communicating effectively.

Researchers indicate that companies which prioritise mental health are sought after by the younger workforce, especially as burnout becomes a greater concern. It is therefore in employers’ best interests to encourage inclusivity and psychological safety in the workplace. Having strategies in place to safeguard employee mental health; pursuing an open dialogue about workload and work challenges; and conducting regular assessments of workplace stressors and burnout risks are considered valuable.

Relax, don’t do it…

One relaxation technique purported to combat the epidemic of work-related stress and burnout is niksen. A Dutch wellness trend that translates as ‘do nothing’, it involves taking the hustle and bustle out of our daily lives for a time. As propounded by Olga Mecking in her 2021 book, Niksen: Embracing the Dutch Art of Doing Nothing, being idle and allowing the mind to wander without feeling the need to be productive or fulfil a purpose is believed to invoke a state of happiness and healing.

While relinquishing control in this manner may be hard for some, others regard it as a lifesaver. Certainly Jürgen Klopp plans to do nothing once the football season has ended – and reportedly for an entire year afterwards.

He may be joined by Leo Varadkar, who recently announced his shock resignation as Irish prime minister. He too, it seems, has been burdened by the weight of responsibility. “Politicians are human beings and we have our limitations,” he said. “We give it everything until we can’t anymore. And then we have to move on”.