Along with other great philanthropic families in Hong Kong history, the Ruttonjees have left an indelible mark on the city. Their legacy has been amazing acts of giving and the establishment of vital charitable foundations. Through their generosity, their footprint on the social fabric is wide, deep-rooted and continues to this day.

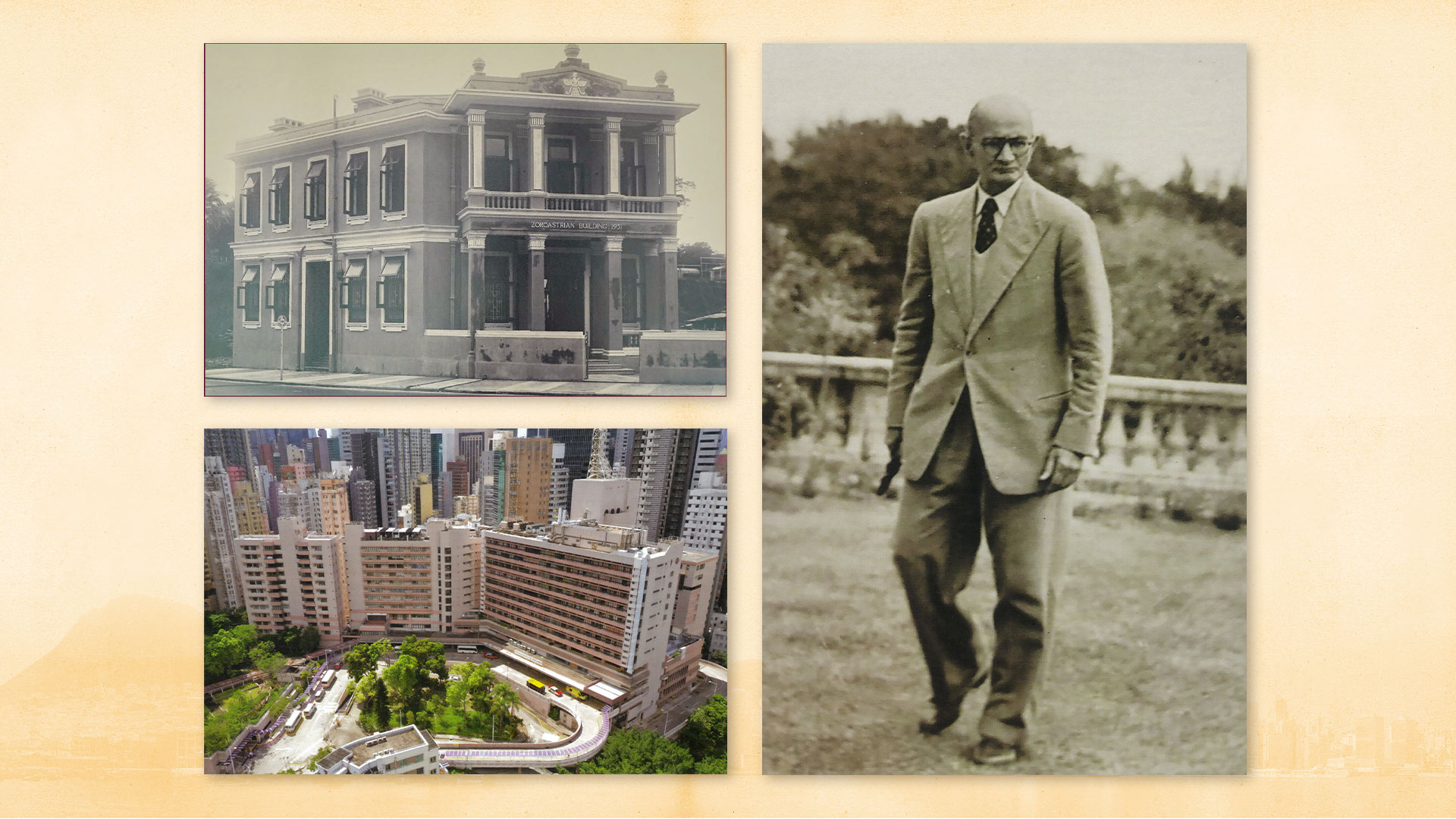

The story of the Ruttonjee family, in many ways, mirrors that of Hong Kong – an epic tale of trade, entrepreneurship, philanthropy and, sometimes, overcoming huge adversity. They are Parsis, an ethnoreligious group originally from Persia (now Iran) that migrated to India, and their patriarch, Hormusjee Ruttonjee, arrived in Hong Kong from Bombay in 1884. He soon began trading in wine, spirits and provisions and founded the family company, H. Ruttonjee & Son, Ltd. Ruttonjee Hospital in Wan Chai, formerly Ruttonjee Sanitorium and dating back to 1949, is the most visible of the family’s many gifts to the city.

The Ruttonjees: Industry, Foresight & Charities, a coffee-table book launched earlier this summer, superbly documents their contributions to the success and well-being of the community. Aside from preserving their own family history for future generations, the tome is intended as a celebration of all those industrious families who have enabled Hong Kong’s rise, no matter their ethnicity or background. It will be placed in public libraries, providing insight to all on how and why the city has thrived.

Ethnic diversity

“Since 1842, numerous ethnic groups have contributed [to Hong Kong] and this should be highlighted to the young local population,” says fourth-generation family member Noshir N. Shroff. He cites the fine examples of many other Parsis in the early years of Hong Kong such as Sir Hormusjee Mody of brokerage company Chater and Mody, and Dorabjee Naorojee Mithaiwala, founder of the Kowloon Ferry Company (forerunner of the Star Ferry).

“The Indians have been traders for a long time and have contributed to the robust Hong Kong economy,” notes Shroff, while stressing that other ethnic minorities, including the Filipinos and the Nepalese, were also instrumental in Hong Kong’s growth over the last century, working alongside the local Chinese population and the British.

Entrepreneurial drive

It was Hormusjee Ruttonjee’s determination to succeed that most impresses Shroff as he surveys his rich family history. He particularly admires his great-great-grandfather’s entrepreneurial spirit, coming to Hong Kong by ship and venturing into segments of the market where he saw opportunities but had little knowledge.

This flair for business was inherited by Hormusjee’s son, Jehangir H. Ruttonjee, who struck out on his own, founding the Hong Kong Brewery and Distillery Ltd. The Sham Tseng brewery he opened in the 1930s was subsequently acquired and operated by San Miguel until 1996.

Noshir Shroff is proud of how Jehangir overcame the many obstacles standing in the way of his vision. He was able to gain not only the necessary water rights from the government but also the support of the villagers. In a testament to his business ethics, he rented their land, one parcel at a time, rather than buying it outright, thus affording them a regular annual income.

Winning hearts

Indeed, it was Jehangir’s sympathetic interactions with the locals all those years ago that, in part, initiated the family book. When its author, Carl Lau, was conducting his doctorate research in the Sham Tseng area, the Ruttonjee name was repeatedly mentioned by village elders.

Shroff retells the story: “The villagers recalled how they wanted a piece of land for a school and clinic, and were prepared to purchase this, but Jehangir told them he would not sell – he wished to give them the land.”

When Lau eventually met Shroff and his family, it was agreed that he would write a book about their history – not just their connection to Sham Tseng but their wider business and philanthropic endeavours.

Enduring hardship

The Japanese occupation of Hong Kong during the Second World War counts among the biggest challenges the Ruttonjee family would face. In these dark times, they housed and fed many fellow Parsis in their two Duddell Street buildings, with all welcome to shelter in the basement during air raids.

Although Jehangir’s prominence and reputation initially earned him the ear of the Japanese, his activities soon began to raise their ire. “Jehangir orchestrated a fundraising campaign for the maintenance and relief of British [civilians held in the internment camps],” relates Shroff. “That was a step too far for the Japanese and resulted in him and his son, Dhun, being imprisoned and brutally tortured.”

Following a turbulent post-war period with the collapse of the stock market and crop failures, Jehangir sold the brewery business to San Miguel ¬– and in characteristic fashion steered the money into numerous charity projects.

Charity after tragedy

The tragic passing of his two daughters, Tehmi in 1944 from tuberculosis, and some eight years later, Freni of cancer, shaped the direction of the family’s charitable legacy. “Despite the grief [of Tehmi’s death], Jehangir provided funds for setting up the Ruttonjee Sanatorium for those affected [by TB]. This building is now the home of Ruttonjee Hospital, a part of the Hospital Authority,” says Shroff, who is exceedingly proud of this project.

Establishing the Hong Kong Anti-Tuberculosis Association in 1948 – now named the Hong Kong Tuberculosis, Chest and Heart Diseases Association, and involved in the management of the Ruttonjee and Grantham Hospitals – has, Shroff believes, made a huge difference to the people of Hong Kong. “Commitment to the association has become a [Ruttonjee-Shroff] tradition with several family members serving on the board of directors,” he says.

After the death of his second daughter, Jehangir erected the Freni Memorial Convalescent Home for the rehabilitation of tuberculosis patients. “Decades later, once TB was in permanent decline, this building became the Freni Care and Attention Home for the aged,” explains Shroff. The 250-bed nursing home, the Rusy M. Shroff Dental Clinic and four Chinese medicine clinics come under the remit of the Hong Kong Tuberculosis, Chest and Heart Diseases Association.

Passing the baton

Jehangir Ruttonjee was also President of the Hong Kong Society for the Protection of Children from 1950-1955, patron of the Family Planning Association of Hong Kong and chair of the Hong Kong Model Housing Society. “He died in 1960, having donated HK$2 million over his lifetime, a considerable sum in those early days,” says Shroff.

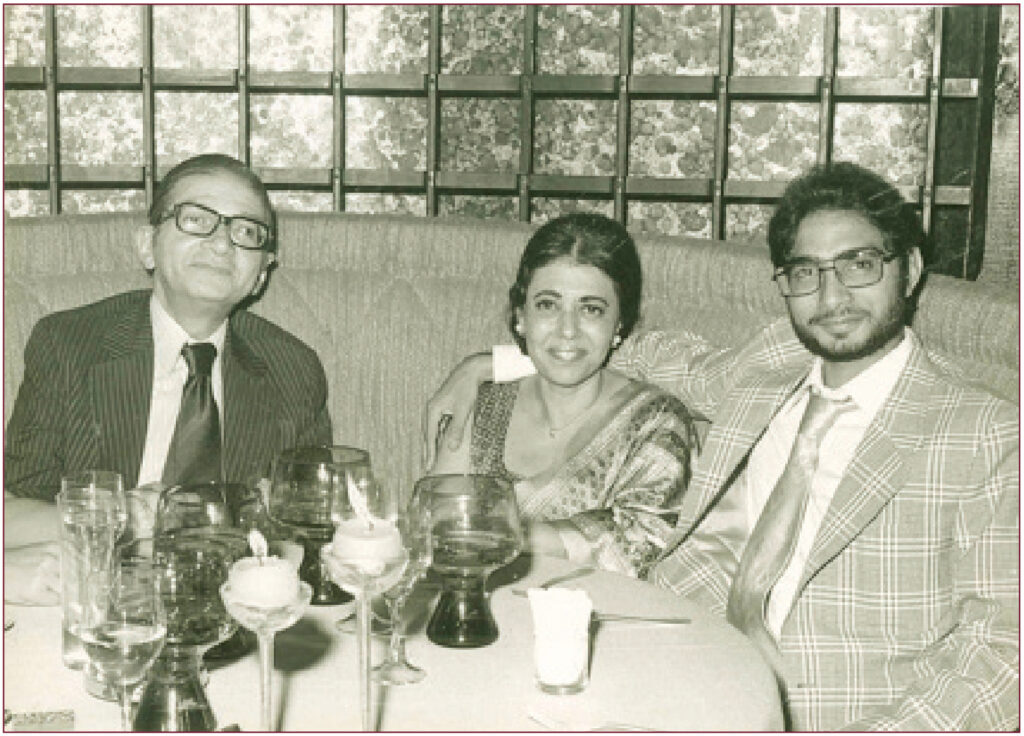

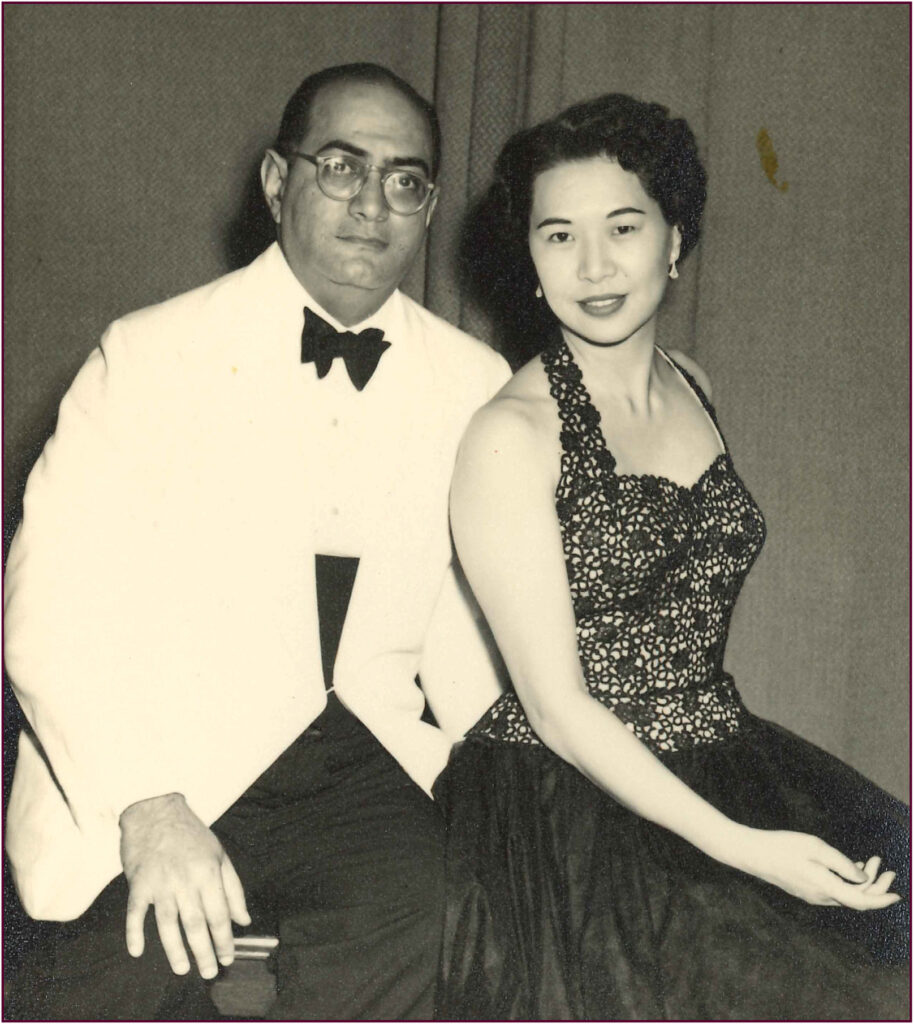

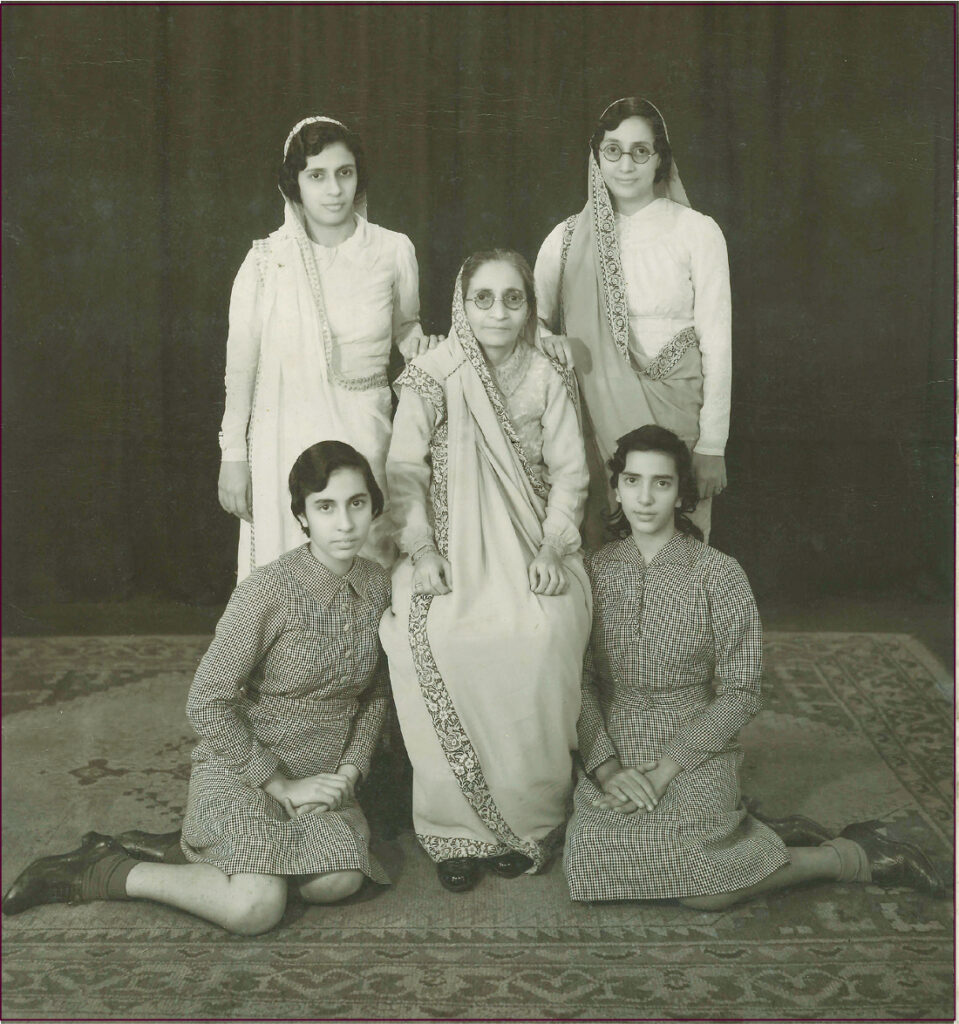

Following the death of his son Dhun in 1974, the mantle as head of the family passed to Rusy Shroff, the nephew Jehangir had adopted along with siblings Beji and Minnie after their father was lost at sea during a typhoon in 1931.

Good deeds

The importance of religious faith cannot be underestimated in the family story. The Parsi community practise Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest monotheistic religions. “The core teachings of Zoroastrianism are good thoughts, good words and good deeds. Charity plays a very big part here,” says Shroff.

Other Parsi families who came to Hong Kong in the 1800s used their fortunes for the good of the city. Hormusjee Mody’s largesse, for example, enabled the founding of the University of Hong Kong.

Shroff believes such acts of benevolence are the Hong Kong way. “Look at the number of charitable foundations established by our local tycoons,” he says. “They have profited by Hong Kong and are giving back. The favourite saying of my uncle, Rusy Shroff, was ‘To live is to give and forgive’.” In 2017, three months before Rusy Shroff passed away at age 100, he established the Rusy and Purviz Shroff Charitable Foundation, which has since given more than HK$200 million to charities in Hong Kong, mainland China and India.